The Block-Justified Text Graphic

There is a graphic technique so common that it goes unnoticed and (as far as I know) un-named. I will call it "The Block-Justified Text Graphic" because it does involve text, of course, that is block-justified (aligned on both the left and right sides) with a graphic impression more pronounced than a simple paragraph in a book.

It is Everywhere

This technique is used frequently for all kinds of graphics:

It is defined by these characteristics:

- At least two lines of text, but with three or more lines the effect is enhanced

- Each line is often a single word, and seldom more than three words

- Text is justified at both the left and right sides, usually by varying the font size of the text on each line

- Sometimes the text is justified by stretching vertically or horizontally, or by varying spacing in between letters.

The net effect is always noticeable (and that is indeed the goal) rather than being unobtrusive as justified text in a paragraph is.

The natural blockiness of the result, with a clearly suggested edge on all four sides, produces a satisfying rectangular form that works well in any sort of frame -- hence its usefulness for book covers, posters, labels, and logos. Although the technique is simple, and perhaps sometimes facile, it is visually powerful and often is all that is needed to make an impression when designing with text.

The power of the block-justified text graphic is that we understand, sometimes consciously, sometimes only implicitly, that this is what someone meant to do. "Oh, I get it," we think, "cool how they made it line up." Just as we recognize the stylized letter "J" in the logo above, we also recognize the alignment of the text as evidence of design intent.

The more clearly we can see that intent in the arrangement of text, the stronger the visual effect. And this graphic technique is about attracting attention rather than receding into the background.

These examples certainly appear to be block-justified text graphics. And perhaps they are. But a close look raises some questions about both intent and execution.

First of all, both have a first line of text in a larger size, with progressively smaller text following. That first line in each example is the name of the person to whom the carving is dedicated -- so it is the most important part. Was the intent, then, simply to emphasize this name over the rest of the text, rather than to create an integrated graphic?

And in both examples the text is not precisely aligned on the left and right sides. Certainly it is more difficult to get this right when carving in stone than when composing on a computer screen. These carvings appear to be the work of skilled artists, though -- probably they could have aligned the edges of the text exactly if they had wanted to.

The simplest explanation may be that perfect alignment was not the goal, and that the idea was instead to use the available space fully while emphasizing the first word. There is enough ambiguity in each of these examples that we cannot be sure of the artist's intent.

Illuminated manuscripts from several religious traditions had, in the first few centuries A.D., been developing as graphic compositions. Those from England and Ireland, though, are really the highest achievement of this art. They present the best examples of designs that (again, imperfectly) appear to be block-justified text graphics.

The page above, from the Durham Gospel, certainly gets close. The right side of all the text is clearly justified. The left sides, though, are just off a bit. They seem to follow the curve of the illuminated graphic letter more than each other -- perhaps that was the point, rather than vertical alignment.

The page above, from the Book of Durrow, is also intriguing. Some of the elements are clearly there, but there are multiple graphic ideas being pursued and none are as simple (or simplistic) as block-justifying a few words.

Also, in both of these examples, the progression of text from largest (with the illuminated first letter) to medium sized (the block justified graphic letters) to smaller (at the bottom of the page) is followed, as it was in the Roman examples. Observing this hierarchy may have been more important, it seems, than creating a visually arresting graphic by varying text sizes from one line to another.

A couple of additional examples (below) from the Lindsfarne Gospels show some of the same characteristics.

Interesting that in both of these examples, the border around the text has a little notch in it at the lower right corner, into which the text intrudes. What is up with that? A case of not planning ahead, or something more meaningful? Perhaps a way to lead the reader's attention on to the next page?

More important for this particular history is the integrated layout of text, graphics, and page border. Clearly the artists who composed these pages intended to use varied text sizes and consistent alignment to create a visual whole. They may not have done it perfectly (and may not have intended to) but the precedent they set was taken up more than a thousand years later by others in England.

Before getting to them, though, there is a long detour through the Dark Ages of graphic design.

Display printing such as appeared on the title pages of books, on posters, and on labels (all much more common now that they could be reproduced cheaply) was generally an all-text affair, without fancy graphics and borders. Variation in text size was used to emphasize certain words, but given the standard sizes of type it would have been difficult to block-justify both sides of a display graphic. So really no one tried.

There are some examples, shown here, of printed items where an attempt of sorts is made to fill the frame by varying type size or spacing. But even more so than with the Roman engraving examples, these are more a case of using the available space than of trying to make precise alignment.

Significantly, though, these examples do depart from the previous strict hierarchy of having the first line with the largest text, then the next few lines of medium size, and so on. Here, text in the middle of the page is sometimes larger to give it emphasis.

This change is an important step -- it was made independently of any desire to align the left and right sides of the text, but by overriding the precedent of text-size hierarchy based on position on the page, the door was opened to allow more freedom in layout.

Some of these posters (such as the example below) come close to block-justifying several lines of text, but that does not appear to be a design goal. Rather, using as much of the width of the page as possible for each line is the priority. This is evident as each line promotes a separate act in the show. A desire to provide publicity for each performer drives the design rather than a visual concept based on alignment.

The limited width of these posters (sized to be glued to a pole, perhaps) required that each line contain only a few words. And the need to give equal billing to each act was an incentive to fill the limited width of the paper, as well as to use different typefaces as a way to distinguish the acts.

So while these posters display many of the characteristics of a block-justified text graphic, one thing missing from many of them is intentional unity of the message. Rather than aligning text in a block to create a unified whole, there is often a desire to separate the message of one line from that of the next.

The example below, an advertisement for F. Ginnett's Circus, presents a more unified design, integrating images and a border with text descriptions that extend across more than one line and that are intended to be read together as a unit. The pieces are all there, and are used emphatically. By the late 19th century, then, this graphic technique had arrived by at least one path.

The natural blockiness of the result, with a clearly suggested edge on all four sides, produces a satisfying rectangular form that works well in any sort of frame -- hence its usefulness for book covers, posters, labels, and logos. Although the technique is simple, and perhaps sometimes facile, it is visually powerful and often is all that is needed to make an impression when designing with text.

Origins and Intentions

Finding the first use of this graphic technique depends on how strictly it is defined, and how much wiggle room is allowed for less than perfect alignment in a pre-computer age. It also depends on interpreting the intent of a long-dead "designer" who was working before that term was ever conceived.

Intentions are important, because often in graphic design the connection between the designer's intent and the viewer's understanding is critical. And that is especially so in the design of logos, signage, and other small, attention-grabbing visuals.

The more clearly we can see that intent in the arrangement of text, the stronger the visual effect. And this graphic technique is about attracting attention rather than receding into the background.

The Ancients

Many written artifacts, from many cultures, generally used only one size of "type" in a document. That is, variation in the size of letters or ideograms was not used to give emphasis to one portion of the text.

One culture that did use a variety of type sizes, though, was the Romans.

|

| 1 A.D. to 30 A.D. - Plaque to Agustus - Herculaneum (Roman) |

|

| 1 A.D. - Epitaph of Mantius |

These examples certainly appear to be block-justified text graphics. And perhaps they are. But a close look raises some questions about both intent and execution.

First of all, both have a first line of text in a larger size, with progressively smaller text following. That first line in each example is the name of the person to whom the carving is dedicated -- so it is the most important part. Was the intent, then, simply to emphasize this name over the rest of the text, rather than to create an integrated graphic?

And in both examples the text is not precisely aligned on the left and right sides. Certainly it is more difficult to get this right when carving in stone than when composing on a computer screen. These carvings appear to be the work of skilled artists, though -- probably they could have aligned the edges of the text exactly if they had wanted to.

The simplest explanation may be that perfect alignment was not the goal, and that the idea was instead to use the available space fully while emphasizing the first word. There is enough ambiguity in each of these examples that we cannot be sure of the artist's intent.

Insular Manuscripts

Medieval manuscripts from England and Ireland, dating from around 650 A.D. to 850 A.D., are some of the earliest examples of graphic design as we know it. The title pages of these manuscripts show an unprecedented integration of text with decoration and a sense of the entire page as a visual entity. |

| 690 A.D. - Durham Gospel |

Illuminated manuscripts from several religious traditions had, in the first few centuries A.D., been developing as graphic compositions. Those from England and Ireland, though, are really the highest achievement of this art. They present the best examples of designs that (again, imperfectly) appear to be block-justified text graphics.

The page above, from the Durham Gospel, certainly gets close. The right side of all the text is clearly justified. The left sides, though, are just off a bit. They seem to follow the curve of the illuminated graphic letter more than each other -- perhaps that was the point, rather than vertical alignment.

|

| 700 A.D. - Book of Durrow |

The page above, from the Book of Durrow, is also intriguing. Some of the elements are clearly there, but there are multiple graphic ideas being pursued and none are as simple (or simplistic) as block-justifying a few words.

Also, in both of these examples, the progression of text from largest (with the illuminated first letter) to medium sized (the block justified graphic letters) to smaller (at the bottom of the page) is followed, as it was in the Roman examples. Observing this hierarchy may have been more important, it seems, than creating a visually arresting graphic by varying text sizes from one line to another.

A couple of additional examples (below) from the Lindsfarne Gospels show some of the same characteristics.

|

| 720 A.D. - Lindsfarne Gospels |

|

| 720 A.D. - Lindsfarne Gospels |

Interesting that in both of these examples, the border around the text has a little notch in it at the lower right corner, into which the text intrudes. What is up with that? A case of not planning ahead, or something more meaningful? Perhaps a way to lead the reader's attention on to the next page?

Before getting to them, though, there is a long detour through the Dark Ages of graphic design.

Typography in the Early Days of Printing

The printing press was of course revolutionary in many ways. The introduction of standard-sized, reusable type increased greatly the number of printed documents, but probably decreased the level of design attention that these documents received.Display printing such as appeared on the title pages of books, on posters, and on labels (all much more common now that they could be reproduced cheaply) was generally an all-text affair, without fancy graphics and borders. Variation in text size was used to emphasize certain words, but given the standard sizes of type it would have been difficult to block-justify both sides of a display graphic. So really no one tried.

|

| 1674 - Poster |

There are some examples, shown here, of printed items where an attempt of sorts is made to fill the frame by varying type size or spacing. But even more so than with the Roman engraving examples, these are more a case of using the available space than of trying to make precise alignment.

Significantly, though, these examples do depart from the previous strict hierarchy of having the first line with the largest text, then the next few lines of medium size, and so on. Here, text in the middle of the page is sometimes larger to give it emphasis.

|

| 1684 - Title Page |

This change is an important step -- it was made independently of any desire to align the left and right sides of the text, but by overriding the precedent of text-size hierarchy based on position on the page, the door was opened to allow more freedom in layout.

|

| 1693 - Title Page |

Some of these posters (such as the example below) come close to block-justifying several lines of text, but that does not appear to be a design goal. Rather, using as much of the width of the page as possible for each line is the priority. This is evident as each line promotes a separate act in the show. A desire to provide publicity for each performer drives the design rather than a visual concept based on alignment.

|

| 1756 - Poster |

Circus Posters

Different type styles and sizes, as well as integrated images and graphics, were used in circus posters to attract attention in a way that might have seemed inappropriate for a serious book cover.The limited width of these posters (sized to be glued to a pole, perhaps) required that each line contain only a few words. And the need to give equal billing to each act was an incentive to fill the limited width of the paper, as well as to use different typefaces as a way to distinguish the acts.

|

| 1838 - Circus Poster |

So while these posters display many of the characteristics of a block-justified text graphic, one thing missing from many of them is intentional unity of the message. Rather than aligning text in a block to create a unified whole, there is often a desire to separate the message of one line from that of the next.

|

| 1878 - Poster |

The example below, an advertisement for F. Ginnett's Circus, presents a more unified design, integrating images and a border with text descriptions that extend across more than one line and that are intended to be read together as a unit. The pieces are all there, and are used emphatically. By the late 19th century, then, this graphic technique had arrived by at least one path.

|

| 1887 - Poster |

At around the same time, graphic artists of a different tradition were getting there too. Whether or not these schools of thought influenced each other is an interesting question. But the end result is very similar.

Arts and Crafts

The Arts and Crafts movement was a reaction to the mass-produced objects that had become common with industrial production. Proponents of this movement argued for thoughtful design and integration of ornament with function.The series of book covers and title pages below depicts an evolution of typographic design leading quite clearly, by the turn of the century, to a full embodiment of the graphic technique of interest here.

|

| 1875 - Walter Crane (Cover) |

The Bluebeard Picture Book (above) although not displaying a fully block-justified graphic, illustrates an early attempt to integrate text with graphics and a border.

|

| 1878 - Walter Crane (cover) |

The Baby's Bouquet, from a few years later, is a step closer.

|

| 1892 - Walter Crane (cover) |

And the example above, A Wonder Book for Girls and Boys, shows the technique in full development. There is no question that the intent here is to align the title text on both sides with the border, and the resulting graphic is a complete entity on the page, equal to the human and bird images as a part of the composition.

|

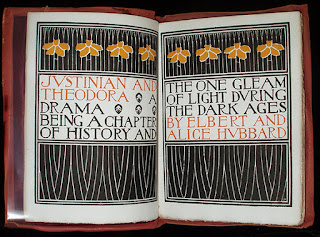

| 1906 - Elbert Hubbard |

|

| 1906 - Elbert and Alice Hubbard (book) |

The two examples shown above, both from the Roycroft Press (a productive Arts and Crafts proponent) show block-justified text graphics in confident, common use. Text size and spacing is varied as needed to align on both sides.

Notably, these examples from designers in the Arts and Crafts movement all appear to be hand-drawn or hand-carved, rather than composed with reusable type. A return to hand work was a crucial component of Arts and Crafts philosophy. It also made block justification of graphic text easier to accomplish, as text size, spacing, and compression or expansion of individual letters could be varied in a way not possible with standard reusable type.

Mainstream Printing

Hand-drawn posters in the early 20th century used this technique as well. These are not in the Arts and Crafts tradition (nor are they explicitly part of the early Modern movement) but the artists who made these works may have been influenced by both. |

| 1915 - WWI recruiting poster |

In the poster above and the well known one below, block justified text is used comfortably as a graphic device. Unlike the Arts and Crafts examples, it is not emphasized but rather fits into the overall composition so easily that it is hardly noticed.

|

| 1917 - WWI recruiting poster |

It may be that there are earlier examples of this technique among hand-drawn signage. As printing of painted or inked artwork was not common before the 20th century, many earlier examples (if they existed) would have been lost. Or it may be that only with the revival of the concept of graphic design did this technique enter the mainstream.

Modernism

The Modern movement, although it glorified machine production, shared with the Arts and Crafts movement an emphasis on design and was a result of the same longing for an integration of form with function.Modern graphic design had none of the ornament that adorned Arts and Crafts graphics. Ornament, if it can be called that, is restricted to differences in color, typeface, or other characteristics that appear to be less applied and more an essential part of the text.

|

| 1923 - Walter Gropius and Herbert Bayer - Bauhaus book cover |

The book cover above, although handmade, does not celebrate that fact as Arts and Crafts graphics do. As with many early modern designs, it may have been the hope of the designer to create a beautiful machine-made graphic, but the design could perhaps only be accomplished by hand using the technology available at the time. This design has all the features of the block-justified text graphic, including a clear intent on the part of the artist to make alignment a focus.

The poster below is definitely machine-printed but less artistically composed. The multiple aligned text blocks give this item a "modern" appearance in keeping with the exposition that it advertises. The limitations of printing technology are apparent -- there is some odd spacing in places and the change in typefaces (using a serif font for the word "exposition") may have been a way to create alignment with the fonts available. Maybe it was the design intent, but if so it is awkward.

|

| 1927 - Exposition poster |

Although block-justified text graphics became increasingly common in the 20th century, they continued to rely on hand-drawn letters rather than use machine type. Type was available in a limited range of sizes, and display fonts in particular would have been rare.

|

| 1935 - Hotel luggage label |

Wood block prints or photographically reproduced drawings or paintings were one-off custom work but they were the best way to create a unique design.

The 1960's

Two examples from the 1960's, coincidentally both for movies about nuclear explosions, show the continued use of this graphic technique in hand-drawn art.

|

| 1959 - Movie poster |

The poster for the Australian release of the movie On the Beach is similar in many ways to early 20th century poster art such as the I Want You recruiting poster. Here, though, text is the only graphic element and the block justified letters are the main focus of attention.

|

| 1964 - Pablo Ferro - Dr. Strangelove movie titles |

The example above, Pablo Ferro's titles for the movie Dr. Strangelove, are an important development. The extreme scaling and stretching of letters emphasizes that they are being forced into alignment and makes the intent of the designer much clearer than previous examples. This technique was used throughout the opening titles for the film.

|

| 1964 - Seymour Chwast - Booth Gin Poster, with cameos by Joan Baez and Bob Dylan |

The example above is just a funny one.

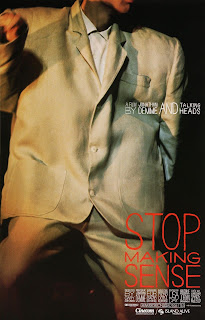

Stop Making Sense

The titles and advertising poster for the Talking Heads concert moving Stop Making Sense, released in 1984, were drawn by Pablo Ferro, using a technique similar to those for Dr. Strangelove. |

| 1984 - Pablo Ferro - Movie titles |

|

| 1984 - Pablo Ferro - Movie Poster |

This may have been the beginning of ubiquitous use of the block-justified text graphic. Although these titles were still hand-drawn, computer typesetting was at this time entering the mainstream of professional graphic design. The Apple Macintosh computer was released in 1984, and the concept of using different "fonts" (a new word for most people) soon became commonplace.

The ease with which fonts and text sizes could be manipulated on screen meant that any designer, and any motivated general computer user, could create graphic layouts that previously had required a high level of skill. The popularity of this concert film (especially among a demographic with artistic inclinations) combined with the availability of this new design tool could have contributed to the fast growth of the block-justified text graphic in the 80's and 90's.

At least that is when, and how, I started using it.

Comments

Post a Comment